Implications of Technological Advancements for Biosecurity

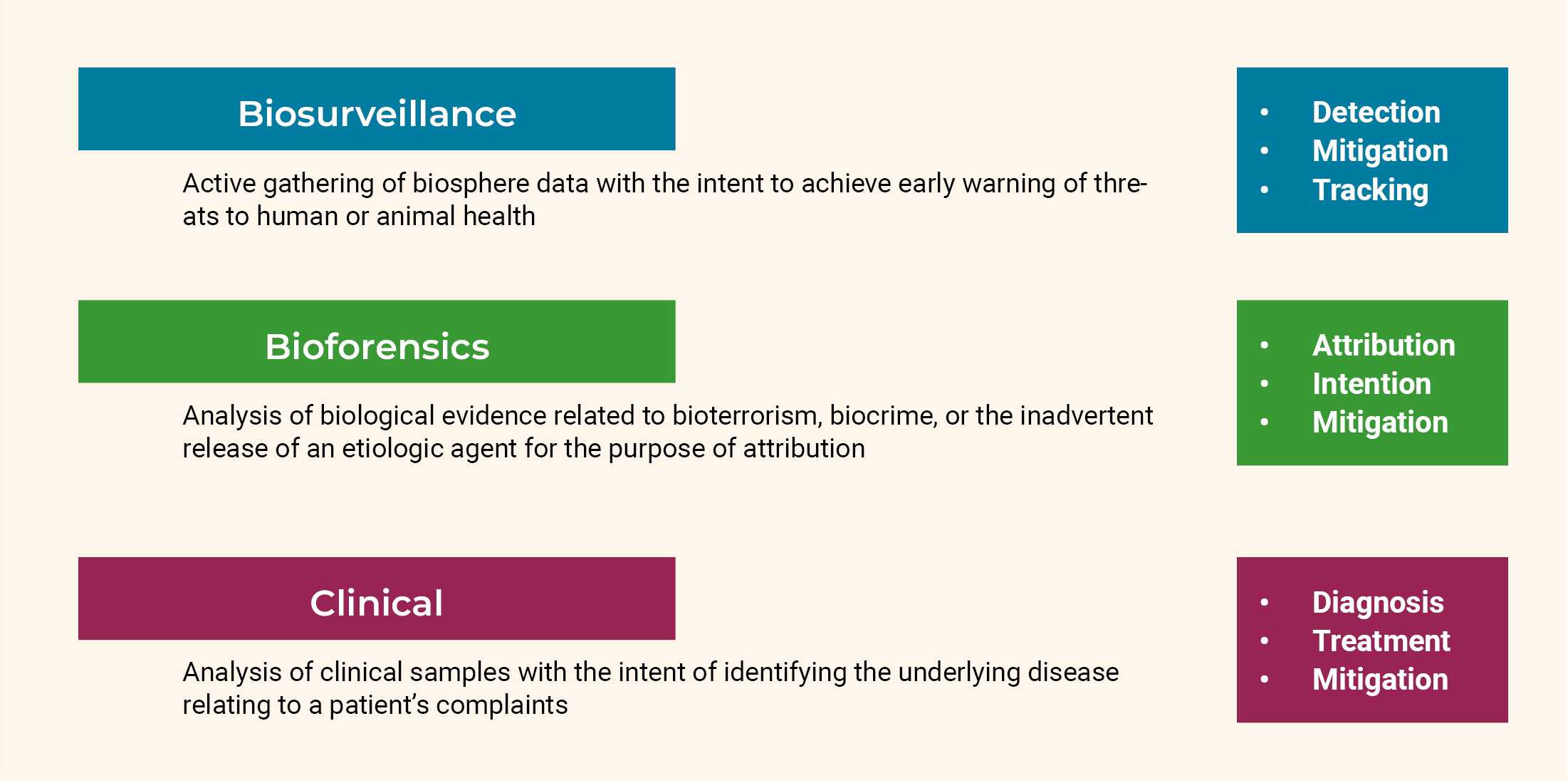

This chapter explores strategies for safeguarding against biological threats. It begins by examining a selection of pathogen identification methods, providing an overview of their technical capabilities, shortcomings, and underlying principles. The second part of the chapter provides a broader analysis of biological attacks, discussing microbial forensics and the potential of attribution of genetic engineering.

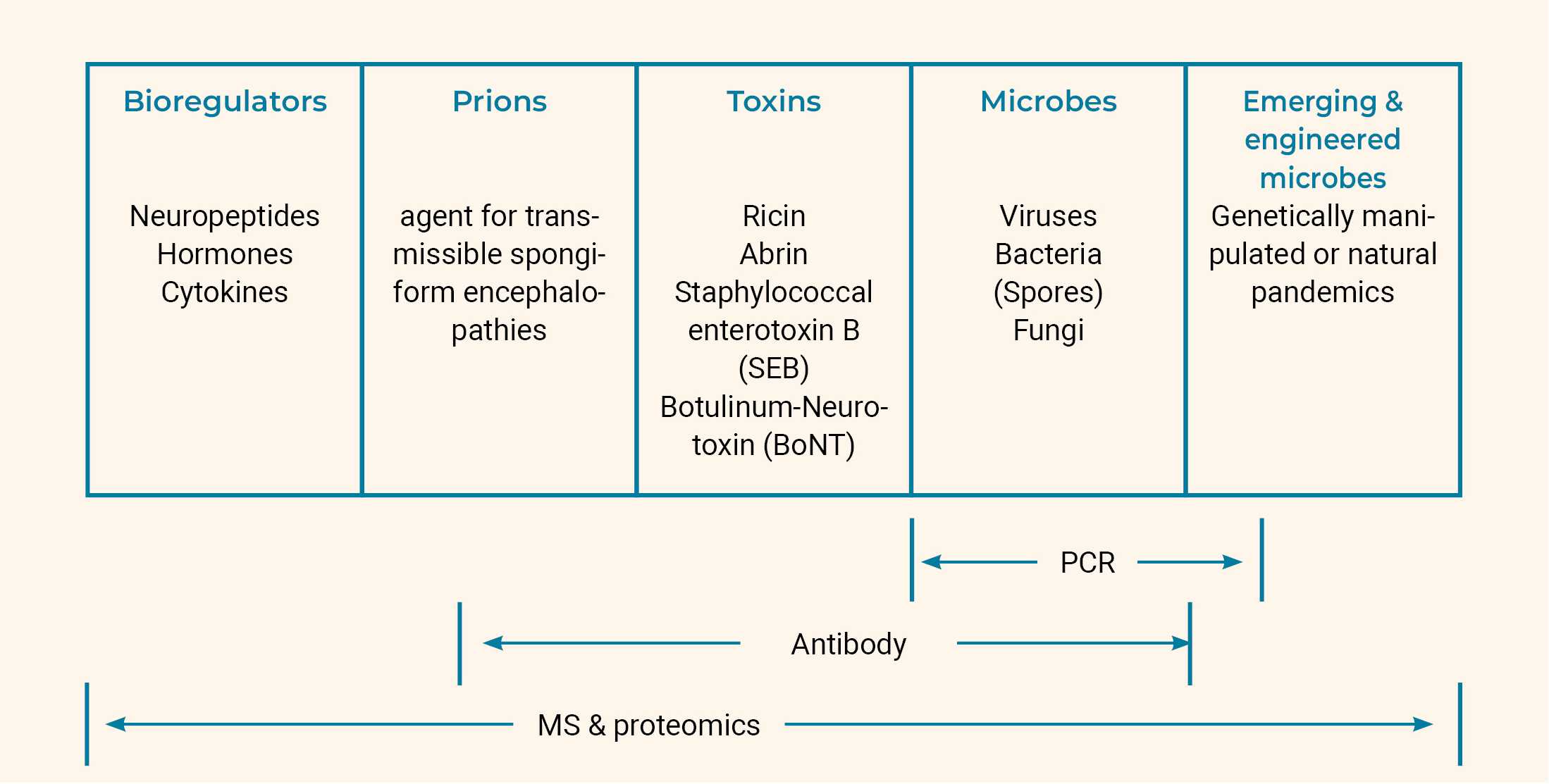

One of the main goals of biodefense is to create rapid, sensitive, and automated technologies capable of detecting and identifying biological warfare agents with high levels of selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy. In terms of identifying pathogens, the ideal (bio)marker would be one that is unique to each biothreat agent and quantifiable. Most pathogen detection systems employ nucleic acids (e.g., DNA), lipids, and proteins as the primary basis for recognition. Common microbial metabolites, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), have also shown promise in pathogen identification.1

The detection technologies focus on a diverse array of methods, encompassing surface characteristics, markers (DNA sequence with a known physical location on a chromosome), proteomic analysis, etc. While culture-based methods, such as genome sequencing, are seen as the benchmark for pathogen detection due to their high sensitivity, they are more labor intensive, costly, and slow, which limits their adaptability for quick response needs. Conversely, molecular methods, such as or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), offer comparable sensitivity, speed, and precision. However, these molecular techniques usually demand highly trained operators. In addition, it is important to note that biowarfare toxins, which lack DNA, cannot be identified through these molecular strategies.

Molecular Detection Methods

Pandemic viruses and pests, like all living organisms, have genomes composed of nucleic acids. Molecular detection techniques depend on these distinct nucleic acid markers which are specific to each biological agent.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

- Still the most popular and widely used technology

- Major advantage is its specificity due to the uniqueness of genomes in living systems

- Greater sensitivity than methods based on antibodies

- Significant drawback is its inability to differentiate between live and dead agents

- To increase throughput, it would be necessary to detect multiple DNA targets simultaneously by combining several sets of primers in one reaction (known as multiplexing2).

Real-Time RT-PCR

- Quantitative method enabling detection and quantification of the nucleic acid simultaneously in any sample3

Effective surveillance systems should operate independently of any specific phenotypes, symptom profiles, or sequences anticipated in future natural outbreaks or bioweapons. Given the limited number of viruses sequenced so far, reliance on existing sequence databases may render detection systems insensitive to novel pandemic agents. Using the abovementioned methods can result in a lack of information concerning the genetic makeup of an organism – a critical factor for bioforensics solutions.

Sequence-Based Methods

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Several experts consider “Amerithrax” (the FBI case name, a portmanteau from “America” and “anthrax”4), the investigation into the post-9/11 biological attacks involving letters containing anthrax spores being mailed to several news media offices and government workers, to have been one of the most instrumental events leading to the significant increase in research funding for (next-generation) sequencing applications.5 While was not used directly in this case, the investigators applied high-resolution and comparative genomics to identify genetic features of the Bacillus anthracis strain from the letters. The capacity to sequence all nucleic acids in a sample for pathogen detection eliminates the need for the prior knowledge about the causative agent that is usually necessary for targeted molecular assays (like real-time PCR). The process starts with the extraction of genomic DNA from the sample. This DNA is then transformed into an , which is subsequently sequenced. The resulting sequence data are compared and aligned against known reference sequences of microorganisms expected to be present within the sample.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS) covers several technologies employed to sequence the nucleotides in complete genomes or specific regions of DNA or RNA.

- The NGS platforms offer massively parallel sequencing, either of clonally amplified or individual DNA molecules.

- NGS sequences DNA through repeated cycles of polymerase-driven nucleotide extensions, producing from hundreds of megabases to entire gigabases of sequence data in a single run.

- NGS experiments generate vast amounts of data, presenting challenges in terms of data handling, storage, and crucially, analysis.

- NGS has revolutionized the exploration of microbial diversity within both environmental and clinical settings.

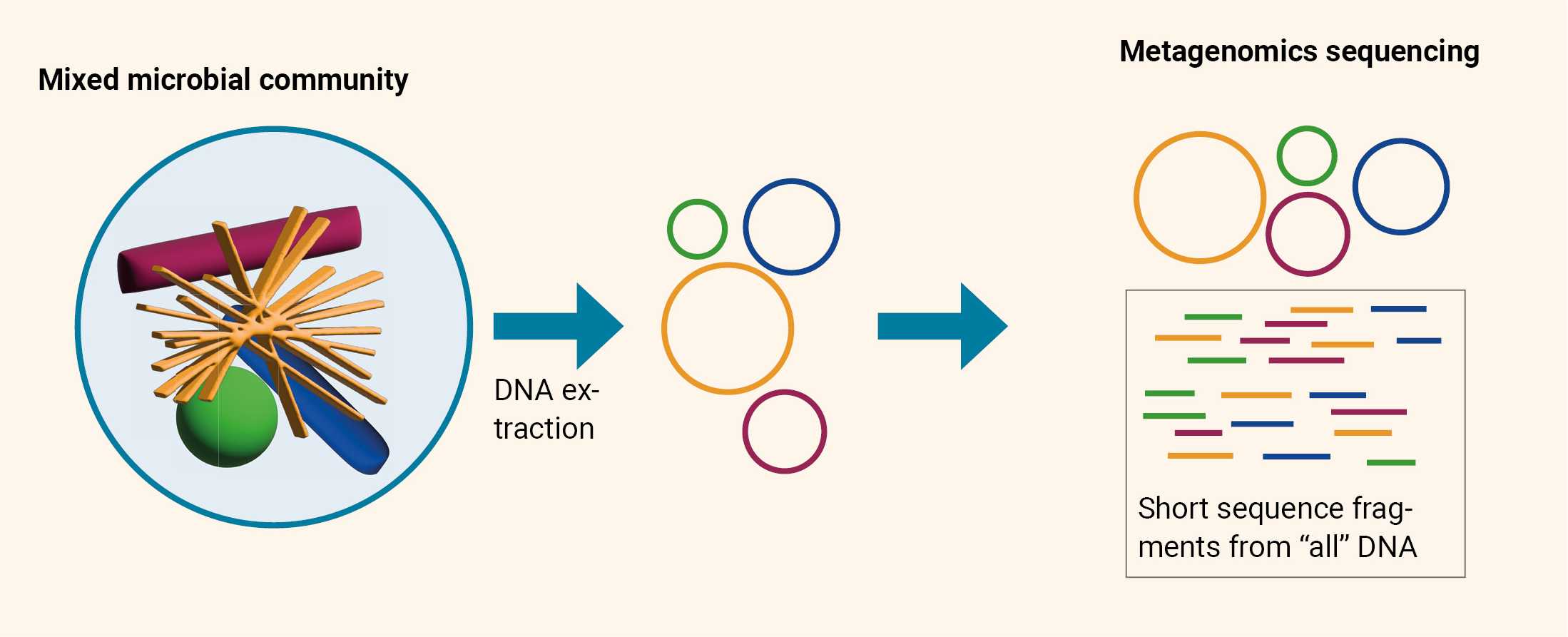

Metagenomic Sequencing

Metagenomic sequencing involves the sequencing of all microbial and host nucleic acids in a sample, without prior selection (culture-independent). This is usually done using the so-called .7 The end goal of metagenomics is to revolutionize microbial surveillance and enhance public health initiatives by proactively screening for threats.

After several rounds of fragmentation and sequencing, multiple overlapping reads for the target DNA are obtained. The overlapping ends of different reads are used to assemble them into a continuous sequence.

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing is unbiased, making it pathogen agnostic. It does not use specific primers or probes, meaning it is possible to detect any pathogen.

- The vast majority of sequenced reads are derived from the human host, making the procedure computationally more complex. Identifying pathogens within these metagenomic libraries becomes a challenging task.

Wastewater Sequencing

The DNA and RNA fragments of pathogens (and other living organisms) are regularly found in bodies of water across the globe, where emerging techniques allow for their identification.9 For instance, SARS-CoV-2 was identified in wastewater several days before the first clinical cases were reported in nearby communities.10 Wastewater sequencing has also detected and identified variants of the virus.11

Samples are collected prior to waste treatment and analyzed in laboratories to identify the type and levels of pathogens within a community. Next-generation sequencing can also be employed for this analysis, offering public health officials a fast and comprehensive method to monitor infections on a large scale. Pathogen surveillance for public health purposes is a regular practice conducted in various settings, such as hospitals, water purification plants, and farms, with a particular focus on areas deemed susceptible to potential disease outbreaks. The main advantage of wastewater sequencing to detect human pathogens is that it preserves privacy.12 It also allows the monitoring of both known pathogens and those yet to emerge, as well as the implementation of early risk mitigation strategies to safeguard human and animal health.

Proteomics and “Lipidomics” Methods

has advanced our understanding of pathogen virulence, structure, and pathogenesis, aiding in disease diagnosis and vaccine creation. It has been used for studying proteins from bacteria and viruses that drive disease transmission in humans and animals – membrane, surface, and secreted proteins are key to pathogenicity. These proteins, serving various critical functions including as enzymes, transporters, and receptors, are central to disease onset and progression.

Analyzing proteomic variations in the pathogenesis of bacteria and viruses enables direct comparisons across different strains of the severity of infections, environmental impacts, and the consequences of genetic alterations.

The most comprehensive approach for the quantitative profiling of proteins, their interactions, and modifications is . The availability of various mass spectrometry platforms, coupled with microbial genomic databases, provides new opportunities.14 The capacity of mass spectrometry to simultaneously analyze multiple analytes in complex matrices such as air, water, culture media, bodily fluids, and food is a significant advantage in the context of biothreat detection and response. Mass spectrometry technologies, combined with other methods, is also often used in chemical forensics for investigative purposes.

- Mass spectrometry is both rapid and sensitive. A typical experiment, including sample collection and preparation, can be completed in minutes, compared to the days required for conventional microbiology or toxicology tests.

- In terms of sensitivity, MS can detect biothreats in samples that contain a small number of intact organisms or a toxin.

Examples of MS Methods for Microorganism Identification

- Platforms such as Matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) are increasingly being used in microbiological research, particularly for diagnostic purposes. These are based on or peptide sequencing techniques.15 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has also approved MALDI‐TOF‐MS‐based platforms, for example, the MALDI Biotyper® (MBT).16 Due to its quick analysis time and low cost of sample processing, the MBT is a reliable option for microorganism identification. By determining the unique proteomic fingerprint of an organism, MALDI-TOF-MS compares the organism against a comprehensive and continuously updated reference library to accurately determine the organism’s identity.

- In some cases, microbial characterization based on other biomarkers, such as lipids, should be considered.17 Here, the progress in another MS technology – ambient ionization mass spectrometry (AIMS) – offers new prospects for the quick, real-time, and precise detection of trace levels of emerging pathogenic microorganisms and toxins, requiring little to no preparation of the sample, which is a huge advantage.18 The “ambient ionization” is an ionization method that generates gas-phase ions in the open air, eliminating the need for chromatographic separation and significantly reducing prior sample preparation.19 This makes it possible to characterize microbial species almost instantaneously.

- Biodefense and pathogen detection companies, such as BioFlyte,19 make portable mass spectrometers for aerosol detection. These MS devices can detect substances in aerosols, including viruses, bacteria, spores, opioids, and others. The latest additions include systems for indoor detection of respiratory pathogens.

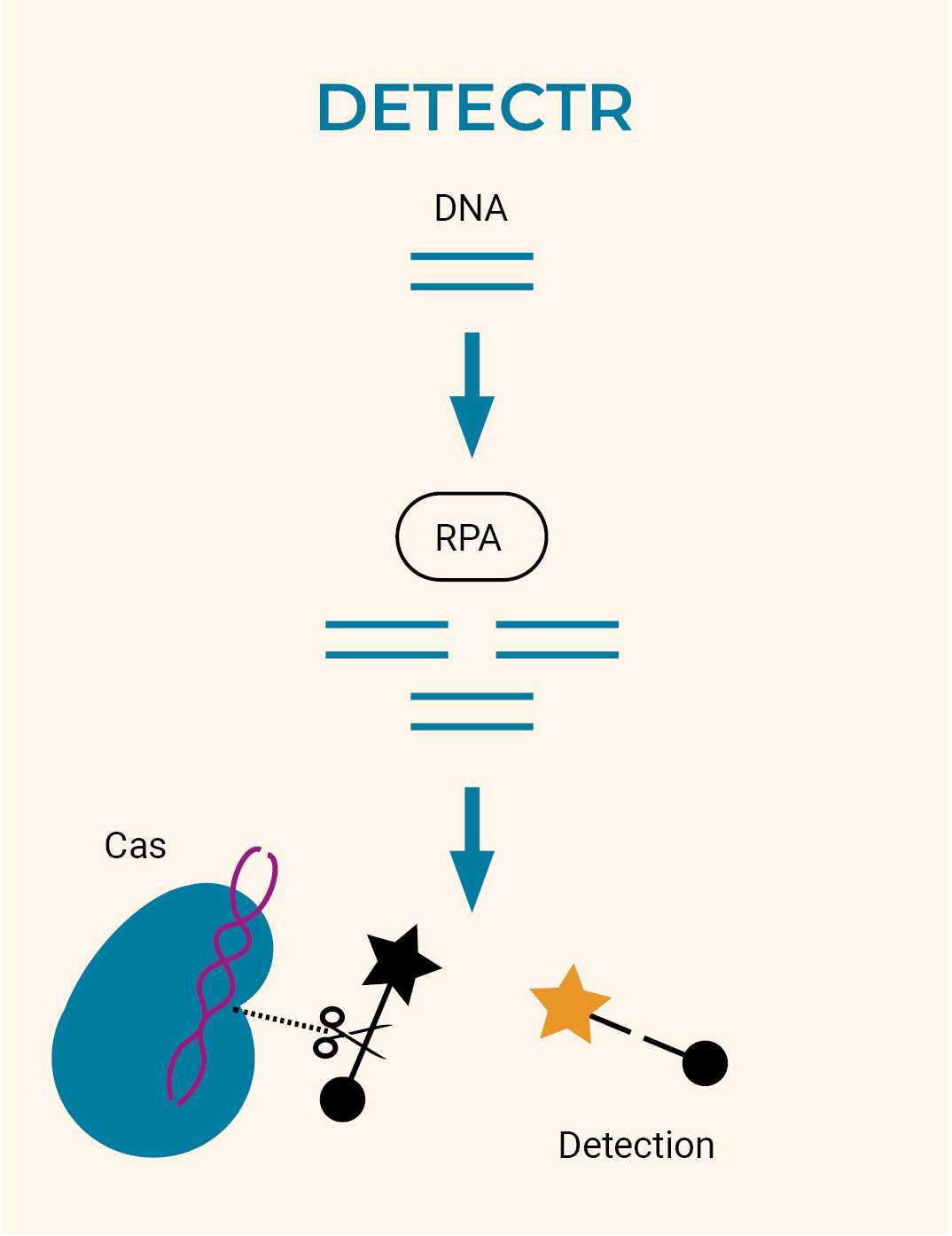

CRISPR-Cas Systems for Diagnostics and Pathogen Detection

In addition to highly targeted modifications of human genes, can also improve speed and accuracy in the detection of viral and bacterial nucleic acids. Two analogous diagnostic systems, known as DETECTR and SHERLOCK, have been designed to detect RNA and DNA sequences, respectively.21 Viral or bacterial RNA or DNA is amplified and then mixed with a CRISPR/Cas system that identifies and cleaves the sequence of interest. After cleaving their target sequences, the Cas protein starts cleaving all other DNAs or RNAs in the solution. Thus, when a reporter sequence is introduced, where the fluorescent signal is quenched by another molecule, Cas will also cleave this complex, resulting in a fluorescent signal that can then be measured.

As an example, Mammoth Biosciences22 creates diagnostics, therapeutics, and protein discovery based on CRISPR technology, promising high accuracy, versatility (pathogen agnosticism), and simple deployment.23 CRISPR-Cas proteins are seen as ideal tools for nucleic acid detection due to their speed and accuracy, using a guide RNA (gRNA) to naturally target DNA or RNA sequences. Genomes of interest can be targeted merely by changing the gRNA’s targeting region, as proved by the rapid adjustment of CRISPR-based diagnostics during the COVID-19 pandemic.24

Microbial Forensics and Genetic Engineering Attribution

Impetus for Microbial Forensics

Despite the fact that microbes have been used as weapons for centuries, the 2001 anthrax letter attacks in the United States caused significant public fear.26 These events highlighted the need for an infrastructure equipped with analytical tools and knowledge bases that can quickly provide investigative leads, help determine who was responsible (attribution), identify the source of the agent, and uncover details about how and where the weapon was produced. As a scientific field, microbial forensics had already emerged before the 2000s, but it was given a significant boost by the Amerithrax events. This subfield of forensic science is focused on examining evidence from bioterrorism acts, biocrimes, or accidental releases of microorganisms or toxins to determine their origins. It is centered on tracing the origin of pathogens to aid in prosecuting individuals responsible for their dissemination. The ultimate goal is to accurately match a sample of uncertain origin to one or more known sources with the highest degree of scientific certainty, while also ruling out other sources. The COVID-19 global pandemic and the uncertainty surrounding the virus’s origin highlight both the urgency and the potential geopolitical ramifications of these technologies. Investigating and attributing biological events is challenging, even four years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Intelligence Community is not unanimous on its origins.

Genetic Engineering Attribution

The risk of biology being misused and causing widespread harm is increasing in step with rapid technological advancements. This, in turn, complicates the challenge of attribution, i.e., being able to determine whether the causative organism was genetically engineered, and if it was, to identify the actor who is behind it. Attribution could provide three principal benefits for security. First, understanding who is responsible, along with their motives and capabilities, helps to adjust response efforts. Second, attribution enables the identification of responsible parties so that suitable civil, criminal, or diplomatic sanctions can be applied. Third, effective attribution coupled with decisive actions to hold perpetrators accountable serves as a deterrent against reckless or harmful behaviors.27 Being caught and held responsible, or the realistic prospect of it, increases the stakes for those involved in illegal biowarfare, bioterrorism, or bioproliferation activities.

In microbial forensics, detailed identification of the microbial agent to the sub-strain level (a strain derived from but different from the characterized strain) is pursued whenever feasible. Laboratory alterations of microorganisms, such as cloning and genetic engineering, leave detectable marks on their genomes.28 These genetic markers, along with observable characteristics, serve as evidence of the intentional creation and dissemination of dangerous pathogens for causing harm. A feature in microbial DNA that is useful for molecular phylogeny analysis is . As genetic markers SNPs are highly stable and informative for lineage studies, though they have low power for identifying individual isolates.

In a genome, the telltale signs of genetic engineering can manifest in several ways. The engineer’s decision-making process is influenced by various factors such as their training, past experience, established practices, and access to resources. These collective decisions form a distinctive “methodological signature,” providing a means to trace design choices back to the likely designer. This may include the presence of foreign genetic material within a specific sequence, as well as unexpected occurrences such as duplications, insertions, or deletions of bases. In addition, sequences encoding antibiotic resistance and short segments known as “scars,” indicating alterations made to a DNA sequence, can serve as flags to help detect engineering. While there is no definitive list of all “engineering sequences,” platforms such as Addgene29 offer extensive databases of molecular tools used for DNA manipulation in laboratory settings. The Addgene dataset, a comprehensive and meticulously curated repository of plasmid sequences along with their authors’ information, serves as a simplified representation of genetic engineering attribution (GEA). While this dataset has been indispensable for advancing GEA methodologies, practical attribution models must eventually expand beyond this initial framework to encompass a broader range of scenarios.

Some experts have raised concerns that knowledge about genetic engineering attribution adds political complexity, as a malicious actor might intentionally choose engineering features to frame another lab or country. In addition, the confidence level required to assert that a specific laboratory is the perpetrator could involve complex diplomatic decisions.

Although GEA methodologies are still in their infancy and attribution remains a complex task, they could nevertheless offer a scientific foundation for verifying and ensuring compliance in BWC discussions.

- Filipiak, W., Ager, C., & Troppmair, J. (2017). Predicting the future from the past: Volatile markers for respiratory infections. European Respiratory Journal, 49(5), 1700264. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00264-2017 ↩

- Kreitmann, L., Miglietta, L., Xu, K., Malpartida-Cardenas, K., D’Souza, G., Kaforou, M., Brengel-Pesce, K., Drazek, L., Holmes, A., & Rodriguez-Manzano, J. (2023). Next-generation molecular diagnostics: Leveraging digital technologies to enhance multiplexing in real-time PCR. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 160, 116963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2023.116963 ↩

- Dung, T. T. N., Phat, V. V., Vinh, C., Lan, N. P. H., Phuong, N. L. N., Ngan, L. T. Q., Thwaites, G., Thwaites, L., Rabaa, M., Nguyen, A. T. K., & Duy, P. T. (2024, February 7). Development and validation of multiplex real-time PCR for simultaneous detection of six bacterial pathogens causing lower respiratory tract infections and antimicrobial resistance genes. BMC Infectious Diseases, 24(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09028-2 ↩

- The United States Department of Justice. (2010, February 19). Amerithrax Investigative Summary. The United States Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/archive/amerithrax/docs/amx-investigative-summary.pdf ↩

- Rasko, D. A., Worsham, P. L., Abshire, T. G., Stanley, S. T., Bannan, J. D., Wilson, M. R., Langham, R. J., Decker, R. S., Jiang, L., Read, T. D., Phillippy, A. M., Salzberg, S. L., Pop, M., Van Ert, M. N., Kenefic, L. J., Keim, P. S., Fraser-Liggett, C. M., & Ravel, J. (2011, March 7). Bacillus anthracis comparative genome analysis in support of the Amerithrax investigation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(12), 5027–5032. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016657108 ↩

- Minogue, T. D., Koehler, J. W., Stefan, C. P., & Conrad, T. A. (2019, March 1). Next-Generation Sequencing for Biodefense: Biothreat Detection, Forensics, and the Clinic. Clinical Chemistry, 65(3), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.266536 ↩

- Quince, C., Walker, A. W., Simpson, J. T., Loman, N. J., & Segata, N. (2017, September 12). Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nature Biotechnology, 35(9), 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3935 ↩

- Lee, M. (2019, September 29). Happy Belly Bioinformatics: An open-source resource dedicated to helping biologists utilize bioinformatics. Journal of Open Source Education, 2(19), 53. https://doi.org/10.21105/jose.000539 ↩

- The Nucleic Acid Observatory Consortium. (2021). A Global Nucleic Acid Observatory for Biodefense and Planetary Health (arXiv:2108.02678). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2108.02678 ↩

- Peccia, J., Zulli, A., Brackney, D. E., Grubaugh, N. D., Kaplan, E. H., Casanovas-Massana, A., Ko, A. I., Malik, A. A., Wang, D., Wang, M., Warren, J. L., Weinberger, D. M., Arnold, W., & Omer, S. B. (2020, September 18). Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nature Biotechnology, 38(10), 1164–1167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z ↩

- Crits-Christoph, A., Kantor, R. S., Olm, M. R., Whitney, O. N., Al-Shayeb, B., Lou, Y. C., Flamholz, A., Kennedy, L. C., Greenwald, H., Hinkle, A., Hetzel, J., Spitzer, S., Koble, J., Tan, A., Hyde, F., Schroth, G., Kuersten, S., Banfield, J. F., & Nelson, K. L. (2021, January 19). Genome Sequencing of Sewage Detects Regionally Prevalent SARS-CoV-2 Variants. mBio, 12(1), e02703-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02703-20; Pérez-Cataluña, A., Chiner-Oms, Á., Cuevas-Ferrando, E., Díaz-Reolid, A., Falcó, I., Randazzo, W., Girón-Guzmán, I., Allende, A., Bracho, M. A., Comas, I., & Sánchez, G. (2021, February 10). Detection Of Genomic Variants Of SARS-CoV-2 Circulating In Wastewater By High-Throughput Sequencing. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.08.21251355 ↩

- The Nucleic Acid Observatory Consortium, 2021. ↩

- Demirev, P. A., & Fenselau, C. (2008). Mass spectrometry in biodefense. Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 43(11), 1441–1457. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.1474 ↩

- Drake, R. R., Deng, Y., Schwegler, E. E., & Gravenstein, S. (2005). Proteomics for biodefense applications: Progress and opportunities. Expert Review of Proteomics, 2(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1586/14789450.2.2.203 ↩

- Rajoria, S., Sabna, S., Babele, P., Kumar, R. B., Kamboj, D. V., Kumar, S., & Alam, S. I. (2020, 10. Februar). Elucidation of protein biomarkers for verification of selected biological warfare agents using tandem mass spectrometry. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 2205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59156-3 ↩

- Bruker. (2024). MALDI Biotyper (MBT). https://www.bruker.com/en/products-and-solutions/microbiology-and-diagnostics/microbial-identification.html ↩

- Su, H., Jiang, Z.-H., Chiou, S.-F., Shiea, J., Wu, D.-C., Tseng, S.-P., Jain, S.-H., Chang, C.-Y., & Lu, P.-L. (2022, April 26). Rapid Characterization of Bacterial Lipids with Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Species Differentiation. Molecules, 27(9), 2772. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092772 ↩

- Ferreira, C. R., Yannell, K. E., Jarmusch, A. K., Pirro, V., Ouyang, Z., & Cooks, R. G. (2016, January 1). Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Point-of-Care Diagnostics and Other Clinical Measurements. Clinical Chemistry, 62(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.237164 ↩

- Venter, A., Nefliu, M., & Graham Cooks, R. (2008). Ambient desorption ionization mass spectrometry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 27(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2008.01.010 ↩

- Bioflyte. (2024). BioFlyte — Biosecurity at Scale. https://www.bioflyte.com/ ↩

- For a summary see: Kocak, D. D. & Gersbach, C. A. (2018). From CRISPR scissors to virus sensors. Nature, 557, 168–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-04975-8 ↩

- Mammoth Biosciences. (2024). Mammoth Biosciences. https://mammoth.bio/ ↩

- Verosloff, M. S., Shapiro, S. J., Hawkins, E. M., Alpay, E., Verma, D., Stanfield, E. G., Kreindler, L., Jain, S., McKay, B., Hubbell, S. A., Hendriks, C. G., Blizard, B. A., Broughton, J. P., & Chen, J. S. (2022). CRISPR‐Cas enzymes: The toolkit revolutionizing diagnostics. Biotechnology Journal, 17(7), 2100304. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.202100304 ↩

- Broughton, J. P., Deng, X., Yu, G., Fasching, C. L., Servellita, V., Singh, J., Miao, X., Streithorst, J. A., Granados, A., Sotomayor-Gonzalez, A., Zorn, K., Gopez, A., Hsu, E., Gu, W., Miller, S., Pan, C.-Y., Guevara, H., Wadford, D. A., Chen, J. S., & Chiu, C. Y. (2020, April 16). CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Biotechnology, 38(7), 870–874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4 ↩

- Cecchetelli, A. (2020, April 16). Finding nucleic acids with SHERLOCK and DETECTR. Addgene. https://blog.addgene.org/finding-nucleic-acids-with-sherlock-and-detectr ↩

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (2020, September 10). Bioterrorism: A Brief History. https://www.selectagents.gov/overview/history.htm ↩

- Lewis, G., Jordan, J. L., Relman, D. A., Koblentz, G. D., Leung, J., Dafoe, A., Nelson, C., Epstein, G. L., Katz, R., Montague, M., Alley, E. C., Filone, C. M., Luby, S., Church, G. M., Millett, P., Esvelt, K. M., Cameron, E. E., & Inglesby, T. V. (2020, December 8). The biosecurity benefits of genetic engineering attribution. Nature Communications, 11(1), 6294. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19149-2 ↩

- Alley, E. C., Turpin, M., Liu, A. B., Kulp-McDowall, T., Swett, J., Edison, R., Von Stetina, S. E., Church, G. M., & Esvelt, K. M. (2020). A machine learning toolkit for genetic engineering attribution to facilitate biosecurity. Nature Communications, 11(1), 6293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19612-0 ↩

- Kamens, J. (2015, January 28). The Addgene repository: An international nonprofit plasmid and data resource. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D1152–D1157. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku893 ↩