Technical, Military, and Political Developments in the Field of Drones

Today’s wars are increasingly characterized by the vital role played by drones. The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020 and the war in Ukraine are often apostrophized as “drone wars.” Yet, the full scope of operations that will be possible with the latest and especially future generations of drones is only just beginning to emerge. There is, however, some confusion surrounding the term “drone,” as many different types are subsumed under it. In this chapter, a technical distinction is first made between different types of drone before outlining the new military possibilities and future developments.

In its drone regulation for the civil aviation sector, the European Union (EU) defines drones very broadly as “all aircraft designed to fly without a pilot on board”.2 This definition therefore includes classic airplanes, but also helicopters (or quadcopters). In the military realm, the term “uncrewed aerial vehicles” (UAV) is often used. The key criterion of a drone, therefore, is that it is an unmanned flying object.

The military differentiates between size, payload, flight altitude, and endurance (“standing time” in the air), though these factors are usually interdependent. Nano and mini drones are only intended for close range, can carry a payload of several grams or even kilograms and usually have flight times of between a few minutes and half an hour, rarely more. Most commercially available drones fall into this category, especially drones for private users and hobbyists. These drones are correspondingly cheap to buy: usually from a few hundred to a few thousand euros. Although originally from the civilian sector (and regulated in great detail in the EU3), the military and non-state armed groups have discovered the dual-use potential of this drone category in recent conflicts.

Drones of the “medium-altitude long-endurance” (MALE) class are characterized by medium flight altitudes (below 9,000 meters), a payload of up to a few tons, and a long standing time of several hours to 2–3 days. Well-known examples include the US MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper, the Turkish Bayraktar TB2, the Chinese GJ-1 Wing Loong, or the Israeli Heron. These drones usually have a turbo propeller drive and are correspondingly slow. They can be controlled directly via radio or indirectly via satellite. Depending on the manufacturer and performance, the price per unit can run into the millions or even multimillions. In addition to a variety of reconnaissance systems, MALE drones often have the ability to drop precision bombs or fire missiles, commonly known as rockets. Due to their design, they are usually easy to detect by radar and easy to fend off with conventional air defense. As such, MALE drones are primarily designed for uncontested airspace in an asymmetric conflict and therefore dominated US operations of the late 2000s and early 2010s as well as the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. Their vulnerability means their contribution in a symmetrical interstate conflict is small as both sides in the conflict have usually developed a comprehensive and powerful air defense system.4

Then there are drones that are characterized by high flight altitudes of over 10,000 meters and long standing times. These are known as high-altitude long-endurance (HALE) drones and their focus is on reconnaissance. Not only are they able to visually monitor large areas of land, but they can also usually capture a broad spectrum of electromagnetic waves, e.g., radio or cell phone signals, and transmit them to the base for analysis. The Eurohawk drone, which is based on the US RQ-4 Hawk, falls into this category.

However, the definition mentioned at the beginning conceals a significant difference which is highly relevant from a military point of view—namely the question of whether a drone was designed to return to a base or the user, and is therefore reusable (reconnaissance drone or weapon carrier), or whether it is intended for single use (“kamikaze drones” or “loitering ammunition”). This distinction is of practical and political relevance: there have been repeated disagreements between Russia and the United States over the interpretation of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), for example, which is now defunct. While Russia argued that US combat drones had characteristics comparable to those of a cruise missile and would therefore fall under the INF ban, the United States argued that, unlike cruise missiles, drones were “two-way, reusable systems” and would thus not be covered by the treaty.5 Indeed, the German government itself argues today: “Loitering ammunition is (...) for single use (shutter) (...). Unmanned systems (UAS), on the other hand, are generally intended for repeated use.”6 This not only shows how important it is to exactly specify the “type of drone” when it comes to questions of arms and export control or deployment restrictions, but also that technical definitions are rarely chosen without ulterior political motives.

3. From the MALE Drone to “Controllable Munition”

Due to their importance in the asymmetric conflicts of the 2000s and 2010s, MALE drones have long dominated the field of combat drones. Since then, they have lost importance as a result of changed conflict situations, specifically the resymmetrization of current conflicts. In Russia’s war against Ukraine, after several initially successful missions, MALE drones are no longer playing a role, especially on the Ukrainian side. Their costs are disproportionate to their survivability and limited benefit and both sides have thus resorted to new techniques and tactics.

Drones as Cruise Missile Replacements

Russia is using large numbers of the relatively inexpensive and technically very simple Iranian Shahed-131 “drones” as GPS-guided cruise missiles, which target military infrastructure or civilians with terrorist intent. This “drone” is therefore similar to the German Fieseler Fi 103 used during the Second World War—more infamously known as “Vergeltungswaffe 1”—both in terms of its purpose and technology (though the Shahed-131 is obviously considerably more advanced). The Israeli drone, too, is relatively easy to defend against, e.g., with anti-aircraft tanks, surface-to-air and air-to-air missiles. The latter was proven by Israel’s successful defense against the Iranian attack, in which more than 170 drones, 120 ballistic missiles, and 30 cruise missiles were detected early, and, according to the Israeli armed forces, 99 per cent of them were repelled.7

On the other hand, Russia’s relatively successful deployment of this type of drone against Ukraine shows that in view of the number of potential targets in a large territorial state, it is extremely difficult and expensive to provide adequate defensive systems, despite extensive and powerful air defense systems. Ukraine, for example, currently only has three Patriot defense systems, but needs a minimum of seven systems and aims to have 25 systems in the long term—while outside of Ukraine, in the whole of Europe, only 32 such systems have been procured to date.8

It is the low production costs of such cruise missile drones, resulting from the simple technology used, that make the—actually technically sophisticated—cruise missile system affordable for many states and represent a major proliferation problem. On a mass scale, these systems are a real threat to technologically advanced states—especially regarding, for example, the fact that a single Patriot missile costs over five million USD. As described above, such systems would however not be included in the definition of drones used by the German Federal Ministry of Defence and would have to be explicitly considered in the relevant international treaties on the restriction of drones.

Drones as Precision Ammunition

The same applies, at least within limits, to the mini drone category. In the war against Ukraine, in particular, this type of drone has gained enormous importance. These lightweight and affordable drones with ranges of around 10 kilometers and hover times of around 30 minutes are often used for tactical real-time reconnaissance. The reconnaissance data can then be entered manually or, as is increasingly the case, also automatically into databases and passed on to, e.g., long-range artillery, so that enemy units on the frontline can be engaged with minimal delay, or misfires can quickly be corrected. The linking of drones and artillery is not new and is technically unproblematic. Nevertheless, for political reasons, most countries refrain from direct data exchange without human control.9 However, such restraint is becoming less and less common on the battlefields in Ukraine.

Small drones can also be equipped with a free-falling grenade to attack positions, guns, or tanks vertically, often at the weakest point. This deployment option is not new either and was first used very successfully against US forces by the terrorist organization “Islamic State” (IS) in Iraq in the 2010s and is also being employed by both sides in Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

With most new models, the operators do not control the drone by sight, but from a first-person perspective via a camera—a method which has earned these models the name “FPV drones” (denoting their “first person view”). This also allows micro drones to function beyond the line of sight, with operators only being limited by the range of their own radio and the battery power of the drive. By using the mobile phone network or the internet for control, micro drones and MALE drones could even be controlled from practically anywhere in the world.

Specially modified civilian “racing drones,” which are characterized by very high speed, acceleration, and maneuverability, are steered with high precision into a potential target at low altitude and detonated there—now often with the aid of virtual reality (VR) goggles. They can now even pose a threat to battle tanks. Here, too, drones are used more as high-precision munitions than as platforms, such that, in line with the Federal Ministry of Defence’s position, we should no longer refer to them as drones but as “controllable munitions”—although the underlying technology is identical and the same model can even be used for reconnaissance and attacks where the drone self-destructs.

Current developments also show that, more and more, drones are being designed and optimized for specific purposes, especially in the micro sector. In Ukraine, in particular, there are now a large number of start-ups experimenting with ever new drone designs—although this creates disadvantages in terms of logistics and maintenance. In addition, drones, or at least spare parts, are increasingly being produced using 3D printing, which further increases the proliferation of such small drone models. The fact that several tens of thousands of these drones were deployed on both sides of Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2023 shows just how significant small drones have become. According to unofficial Russian sources, it was small drones that stopped the Russian advance in Ukraine. On average, six to ten drones were enough to destroy a Russian tank.10 At the beginning of the year, Ukraine then announced that it would increase production to one million(!) of these FPV drones in 2024,11 while at the same time a group of European countries promised to supply Ukraine with a further million drones in 2024.12

The knowledge of how to manufacture small drones with a small payload has now proliferated, and practically every aviation department at any university is able to assemble its own drones from freely available components in a very short time. The civilian market is also booming: while global sales in this segment were estimated at USD 8.8 billion in 2022, sales are expected to reach almost USD 55 billion in 2030.13 Accordingly, civilian and military innovation in the field of smaller drones are currently mutually dependent, but the military, in particular, is benefiting enormously from the dual-use nature of the micro drone.

Drone Defense

In contrast to the large models, small drones are difficult to defend against due to their size and associated maneuverability. For soldiers, this means constant, extreme psychological stress, as it is often impossible to tell whether the high-pitched whirring noise, which indicates a nearby drone and therefore great danger, is coming from an enemy drone or one of their own. In addition to physical defense, where nets or lasers are now being experimented with alongside projectiles, jammers and other electronic warfare systems are often used to disrupt communication between pilots and drones. Such systems are also used in the civilian sector and were one of the main defenses used by the German police during the 2024 European Football Championship.14

The condition for the success of such defensive measures is that the drones are still controlled by humans—which remains the case for most models. However, the “loitering munitions” described above are also used, i.e., drones that circle over a certain area, look out for targets, e.g., radar positions, and then attack them—either with human approval or independently—meaning they are barely dependent on human control any more. As such systems are less susceptible to electronic jamming, there is pressure for ever greater automation, which in turn increases the pressure to use human-independent defense systems—the classic cat-and-mouse game of offense and defense.

Current Technical Developments

Autonomous Functions

The current generation of commercially available civilian drones already contains extensive algorithms that can certainly be understood as “AI,” even if they are not based on deep learning. Thanks to extensive auxiliary functions such as automatic stabilization and orientation in space, it has become very easy to control modern micro drones, allowing even relatively inexperienced pilots to operate these drones safely. This fuels the risk of proliferation associated with these systems.

Swarms of Drones

While military drones currently still mostly operate alone, it is already foreseeable that networked use as swarms15 of inexpensive drones, in particular, will become increasingly common in the future—especially if this makes it possible to overload defense systems and thus, as the military jargon goes, “achieve an effect.” Every month we are seeing new records being set in the civilian sector with coordinated swarms of drones, and practically no major event is complete without an impressive drone show. At the time of writing, the world record stood at 5,293 drones, which conjured up coordinated three-dimensional figures in the night sky16 —even if control is usually still centralized via a main computer and not decentralized between the drones. The record is usually held either by the USA or China.

The fact that the military has recognized the relevance of drone swarms is shown, for example, by the U.S. Department of Defense’s “Replicator” project, which aims to procure “thousands of all-domain, attritable, autonomous swarming robots” by 2025 for possible use against China in the Pacific region.17 The corresponding budget for 2024 and 2025 envisages total expenditure of around USD 1 billion. But resources are also being invested into developing swarms of small drones that can attack tank columns or be deployed against infantry, for example. Artificial intelligence plays an important role here, too, as the aim is for the swarms to be able to organize themselves without external influence or even act without a GPS signal. However, drone swarms do not necessarily have to have high AI capabilities in order to bring even powerful actors to the brink of their defense capacities, simply by overburdening them, as described above.

Drone Carriers and AI Pilots

The importance of drones is demonstrated by the fact that China is now in the process of building the first dedicated and appropriately optimized “drone carrier.” The Chinese ship is probably around a third of the size of a conventional aircraft carrier and appears to be suitable for carrying MALE-category drones, but not manned aircraft.18 This means that China and Iran, the latter having adapted a civilian transport ship, are currently the only countries that have such a maritime unit.

These examples of pure drone carriers will certainly set a precedent, especially as the mixed operation of drones and manned aircraft on classic aircraft carriers is not a trivial undertaking but involves considerable effort.19 In the meantime, a refueling drone, the MQ-25 “Stingray” developed by Boeing, has been in test operation on a US aircraft carrier for a long time, a project which was, however, not without its problems and delays. Nevertheless, the Navy is holding on to the project.20 One of the reasons for this was that the test operation of the Stingray provided valuable technical data—and this still needs to be understood on a larger scale. After all, it is already possible to make classic manned jets fly largely autonomously—including take-off and landing—simply by installing additional computers—. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which funds high-risk research projects, is currently working on various initiatives to enable AI-supported aerial combat. While in 2020, a simulated dogfight was won 5:0 by AI against an elite human pilot and caused a stir among experts, in September 2023 it was real jets that competed against each other in a simulated dogfight controlled by artificial intelligence and humans.21 This time, DARPA did not want to reveal who came out on top22—but it shows that a new operable class of drone, the unmanned fighter jet, could enter the battlefield in the not too distant future. A similar battle had already been fought in China a few months earlier—here the human pilot did not have a chance against AI. In the future, combat drones on aircraft carriers could significantly increase the range and striking power of traditional aircraft carriers.

Regulation and Outlook

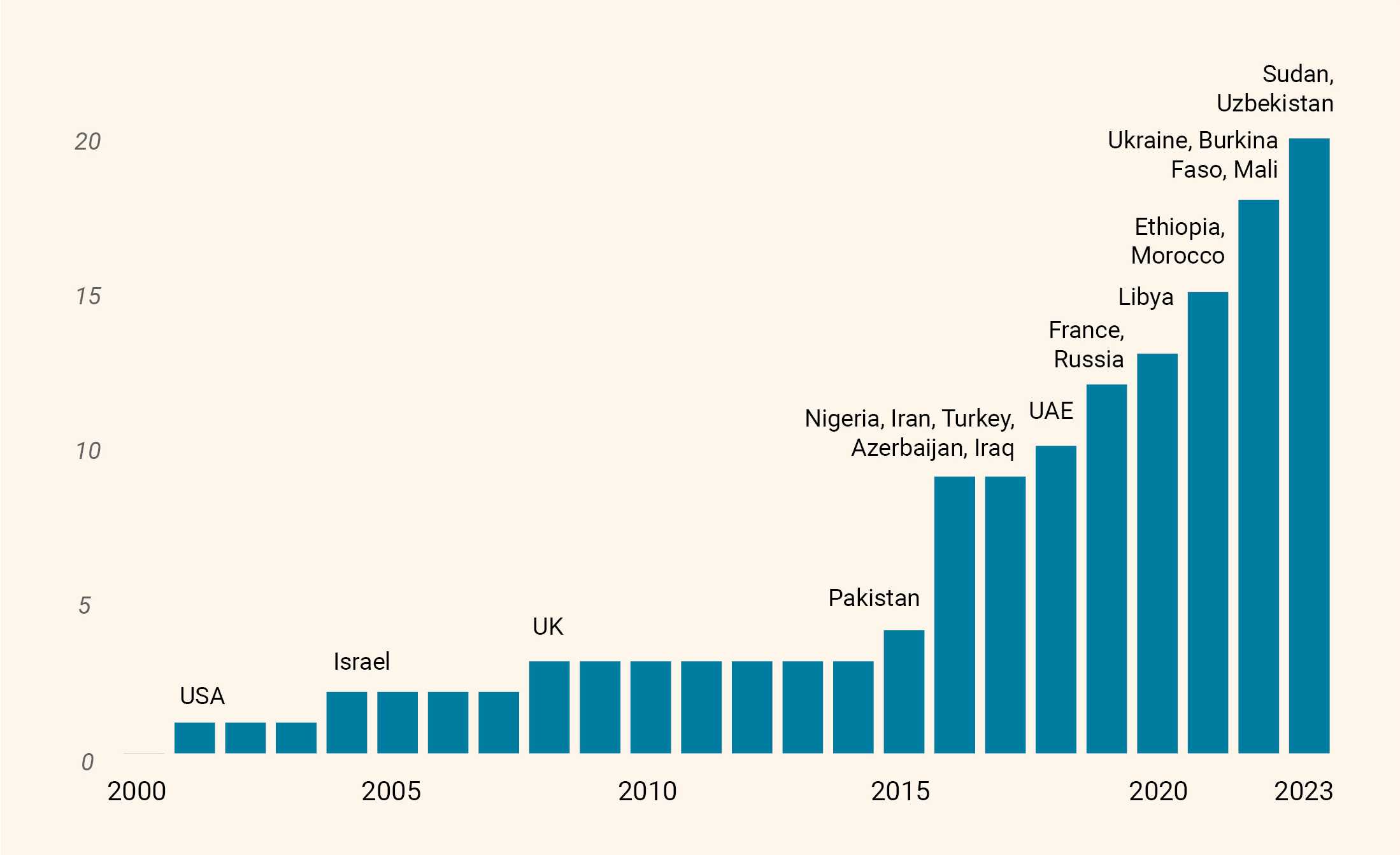

In recent years, new technical developments have led to a rapid increase in the use of drones, and not only in the civilian sector. In the military sector, in particular, drones have become considerably more important in a variety of different forms. The technical exchange between civilian and military use plays a key role here, and many innovations in this area come from the civilian sector. In the area of large systems, it seems only a matter of time before unmanned fighter jets will be used—the military advantage over manned systems is simply too great. Yet, the field of drones is only weakly regulated internationally and the specific regulations that do exist essentially relate to asymmetric export controls. Despite, or perhaps because of, the ubiquity of small drones in the civilian sector, many actors are unaware that drones have long been categorized as dual-use products and fall under export control guidelines. For example, the Wassenaar Arrangement imposes restrictions on drones if they exceed a certain maximum flight duration and can operate in winds of force 6 or more, as well as on technologies that allow formerly manned aircraft to be flown by remote control. Significantly larger drones with a payload of over 500 kg and ranges of over 300 km are still covered by the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) and their export is strictly regulated by an “unconditional strong presumption of denial.”23 However, in 2020, the USA moved to no longer subject drones with a speed of less than 800 km/h to this strict export regulation—a view that President Biden’s administration has since endorsed.24

There are currently no other regulations on military drones, let alone a ban. Although there was a German “initiative to agree international framework principles for the military use of armed drones” in 2020, this was buried relatively quickly and quietly. The window of opportunity appears to have been missed.

There is a similar threat when it comes to increasing autonomy in drones and other weapon systems. In view of the strong technical dynamics, it is questionable whether binding international regulations or even bans on “autonomous weapon systems” will be introduced, as this would then also include unmanned fighter jets, for example, if the attacks are not controlled by humans.

One thing is certain: small drones are the current “weapon of choice,” especially for economically weaker actors. Difficult to defend against in large numbers, easy to reproduce, and benefitting from dynamic technical advancements due to civilian developments, drones can not only significantly disrupt regional balances of power—they also pose a considerable threat to technologically advanced and powerful actors. Investment in a broad portfolio of drone defense measures is therefore mandatory.

- This text is based in part on considerations already presented in the Peace Report 2024 and adopts some sections, see: BICC Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies, IFSH Institut für Friedensforschung und Sicherheitspolitik an der Universität Hamburg, INEF Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden, PRIF Leibniz-Institut für Friedens- und Konfliktforschung (Eds.). (2024). Friedensgutachten 2024. transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839474211 ↩

- European Union. Unmanned aircraft (drones). https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-modes/air/aviation-safety/unmanned-aircraft-drones_en ↩

- European Union. Easy Access Rules for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (Regulations (EU) 2019/947 and 2019/945). European Union Aviation Safety Agency. https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/easy-access-rules/easy-access-rules-unmanned-aircraft-systems-regulations-eu ↩

- Calcara, A., Gilli, A., Gilli, M., Zaccagnini, I. (2022, July 31). Air Defense and the Limits of Drone Technology. Lawfare Media. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/air-defense-and-limits-drone-technology ↩

- See quote by Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense Brian McKeon in https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43832, S. 28. ↩

- Bundesregierung. (2024). Loitering Munition für die Bundeswehr. Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage des Abgeordneten Gerold Otten und der Fraktion der AfD (Drucksache 20/10266). Deutscher Bundestag. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/104/2010456.pdf ↩

- Israel Defense Forces [@IDF]. (2024, April 14). 300+ launches. 99% interception rate. This is the breakdown of Iran‘s attack last night: [Image attached] [Post]. X. https://x.com/IDF/status/1779503384434819454 ↩

- Häsler, G., & Rüesch, A. (2024, June 21). Die Ukraine erhält weitere Patriot-Abwehrsysteme und wird bei künftigen Lieferungen bevorzugt. Neue Züricher Zeitung. https://www.nzz.ch/international/ukraine-erhaelt-weitere-patriot-systeme-und-prioritaet-bei-lieferungen-ld.1836207 ↩

- Personal conversation with members of the Bundeswehr. ↩

- Samuel Bendett [@sambendett]. (2023, December 31). 1/ THREAD on the impact of small quadcopters in the Ukraine war over the past year – based on my earlier [Image attached] [Post]. X. https://x.com/sambendett/status/1741454000463941648?t=COXJ91RR3iQLVdKvsRYaxQ&s=19 ↩

- The Kyiv Independent news desk (2024, February 25). Fedorov: Ukraine to produce 1 million drones per year. The Kyiv Independent. https://kyivindependent.com/fedorov-ukraine-to-produce-1-million-drones-per-year/ ↩

- Martin, T. (2024, February 15). European coalition bids to deliver 1 million drones to Ukraine. Breaking Defense. https://breakingdefense.com/2024/02/european-coalition-bids-to-deliver-1-million-drones-to-ukraine/ ↩

- Fortune Business Insights. (2024, August 12). Commercial Drone Market Size, Industry Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis (...). https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/commercial-drone-market-102171 ↩

- Kalus, T. (2024, June 8). Reul: Drohnen-Abwehr bei der Fußball-EM ist startklar. WDR. https://www1.wdr.de/nachrichten/drohnenabwehr-stoersender-em-reul-100.html ↩

- Verbruggen, M. (2019, December). The Question of Swarm Control: Challenges to Ensuring Human Control over Military Swarms. Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Papers, (65). ↩

- Mackenzie, W. (2024, May 13). Largest Drone Swarm Display Sets New World Record. Unmanned Systems Technology. https://www.unmannedsystemstechnology.com/2024/05/largest-drone-swarm-display-sets-new-world-record/ ↩

- Luckenbaugh, J. (2024, January 4). Replicator Initiative Looks to Swarm Through ‘Valley of Death’. National Defense Magazine. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2024/1/4/replicator-initiative-looks-to-swarm-through-valley-of-death ↩

- Sutton, H I. (2024, May 15). China Builds World’s First Dedicated Drone Carrier. Naval News. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/05/china-builds-worlds-first-dedicated-drone-carrier ↩

- Schwartz, S., Reuter, C. (2020). 90.000 Tonnen Diplomatie 2.0: Die Integration von unbemannten Systemen in den operativen Flugzeugträgerbetrieb am Beispiel der X-47B. Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik, 13(1). doi: 10.1007/s12399-020-00803-y ↩

- Tegler, J. (2024, January 26). Despite Delays, Navy to Accelerate Delivery of Unmanned Tanker. National Defense Magazine. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2024/1/26/despite-delays-navy-to-accelerate-delivery-of-unmanned-tanker ↩

- Defense Advanced Research Project Agency. (2020, August 26). AlphaDogfight Trials Foreshadow Future of Human-Machine Symbiosis. United States Department of Defense. https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2020-08-26 ↩

- Decker, A. (2024, April 19). An AI took a human pilot in a DARPA-sponsored dogfight. Defense One. https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2024/04/man-vs-machine-ai-agents-take-human-pilot-dogfight/395930/ ↩

- Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies. (2023. December 1). 9.A.12.a and 9. A. 12. b. https://www.wassenaar.org/app/uploads/2023/12/List-of-Dual-Use-Goods-and-Technologies-Munitions-List-2023-1.pdf ↩

- Kimball, D. G. (2020, September). U.S. Reinterprets MTCR Rules. Arms Control TODAY, 50. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-09/news/us-reinterprets-mtcr-rules ↩