Technological Implications of AI in Biorisk

AI has increasingly been a topic of discussion in conventional arms control, battlefield management, and data analysis, as seen in contexts such as Ukraine and Gaza. Simultaneously, the growing influence of AI in various fields highlights the need for renewed discussions on policy and governance. This chapter aims to explore the potential implications of the convergence of biological sciences with AI. First, the numerous benefits that can arise at this intersection will be examined (with examples in biodefence and bioweapons/genetic engineering attribution). Then an analysis of the associated risks and suggestions for mitigation will be provided. Though some of these risks could be generalizable across biology and chemistry (e.g., using AI for a molecule/sequence design), this report focuses largely on the biological risks.

Convergence of AI and Biological Sciences: The Benefits

Recent significant advances in artificial intelligence (AI) offer enormous benefits for modern bioscience and bioengineering. Artificial intelligence can aid in rapid vaccine and therapeutics development, contribute to material science, benefit the economy, and help fight climate change.1

AI in Pandemic Preparedness

Enhancing pandemic preparedness and response also requires leveraging advanced technologies such as AI to optimize outbreak reporting and analysis.2 By efficiently processing data from outbreak reports and analyzing information from returning travelers, AI tools can model the frequency of infectious disease importation and trace its origins. For example, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control hosts tools for the analysis of infectious disease surveillance data.3 Routine surveillance data undergoes statistical analysis to detect any fluctuations in disease incidence, enabling the early identification and investigation of potential outbreaks. When combined with genome sequencing, this approach becomes crucial for identifying outbreaks and uncovering persistent reservoirs of pathogens.

Further, AI plays a key role in predicting the risk posed by (new) pathogen strains.4 Rapid DNA analysis facilitated by AI tools enables scientists to identify potential pandemic pathogens and high-risk variants before they escalate into widespread outbreaks.

AI in Pathogen Surveillance

Metagenomic surveillance, such as monitoring wastewater, can identify pathogens circulating in communities.5 With the vast amount of data generated, AI tools such as anomaly detection can help identify (new) threats.6 offer a cost-effective alternative to DNA sequencing for ongoing monitoring of infectious diseases.7 Designing panels capable of detecting numerous pathogens can be complex, but AI optimization techniques can streamline the process.

AI in Genetic Engineering Attribution

Recent advancements indicate that AI tools can effectively identify genetically engineered organisms and attribute them to their laboratory of origin. Collectively, the design decisions of a biological engineer – choice of promoter (transcription start site of a DNA sequence), optimization of code, selection of functional genes, choice of method used for cloning – are the “signature” of that designer.8 Several new techniques have been developed that aid in collecting these signatures, and analyzing them requires complex data analysis that could be advanced with machine learning and AI tools. While these tools hold promise in identifying actors who design harmful biological agents, their effectiveness in attribution may be compromised if actors can manipulate design choices to evade detection.

AI in Synthetic Biology

Synthetic biology offers significant potential to address important societal challenges. However, a major obstacle is our current inability to predict biological systems as precisely as we can predict and simulate physical or chemical ones. This limitation has both practical and fundamental implications. Practically, we cannot design biological systems (e.g., proteins, pathways, cells) to specific requirements (e.g., binding affinity, production rates). Fundamentally, we lack a deep understanding of the mechanisms that produce observable characteristics or traits of organisms. Artificial intelligence and (ML) hold promise in enhancing the predictive power needed in synthetic biology and can be applied throughout the synthetic biology process.

For example, in the past two decades, various machine learning tools have been developed to aid enzyme engineering by simplifying approaches and reducing the screening efforts required. Machine learning can process information about enzyme sequences and properties, inferring novel information that is likely to enhance or refine these properties. These algorithms have numerous applications in synthetic biology, including optimizing genetic and metabolic networks, directing enzyme evolution, predicting kinetic properties of uncharacterized enzymes, and even the de novo design of entire proteins.

Risks of AI-Bio Convergence

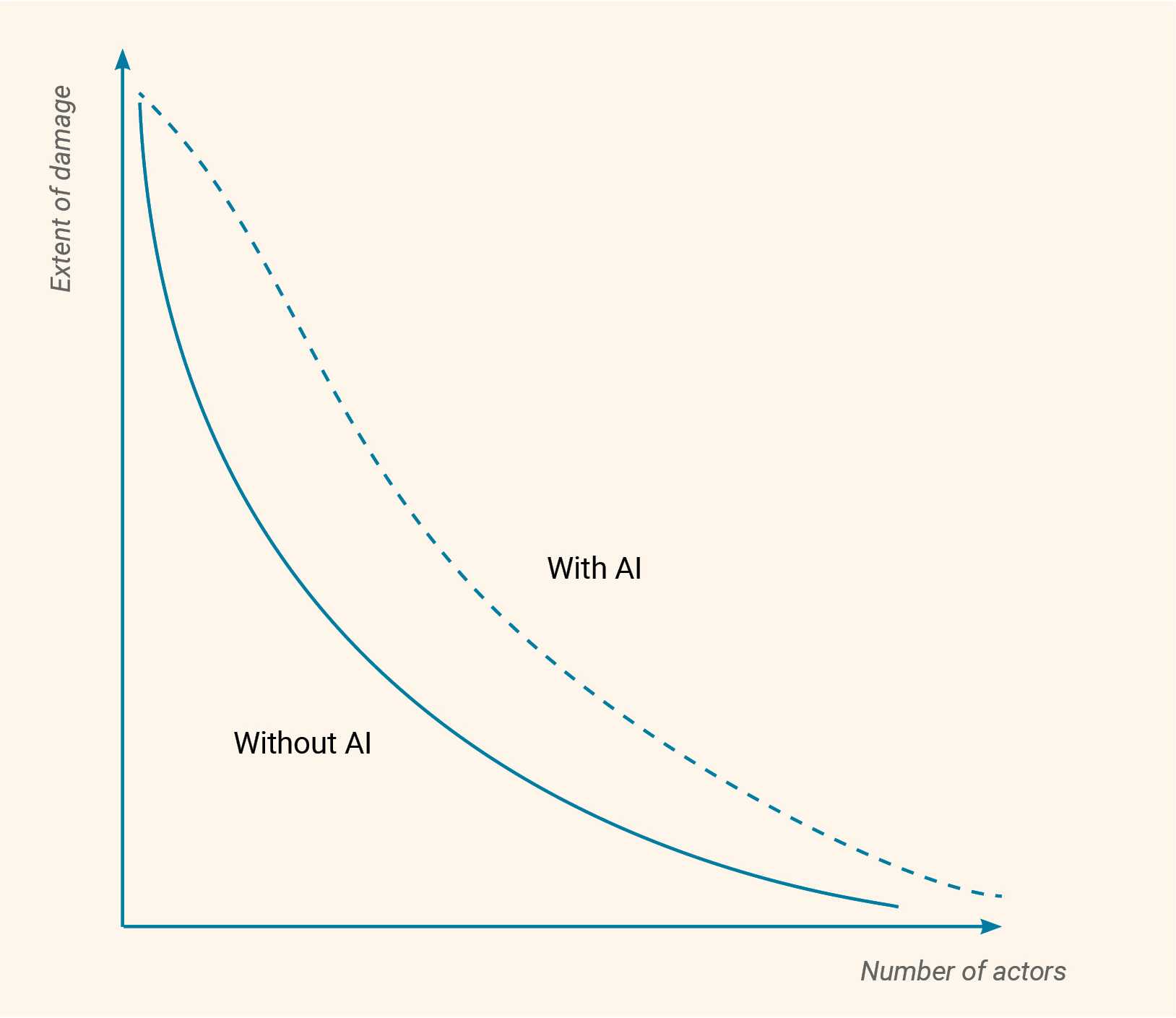

Experts analyzing the potential risks that AI methods pose for the life sciences are currently focusing on two main questions.9 First, do advances in AI tools reduce the barriers to engineering pathogens? Some experts suggest that they do.10 Second, which AI models and tools are at greatest risk of misuse?

Artificial intelligence tools posing a potential security risk could be classified into three categories:11 large language models (LLMs), biodesign tools (BDTs), and AI-enabled automation of life sciences. While these categories might be beneficial in assessing the specific potential biosecurity risks posed by each, the lines between these capability types are becoming increasingly blurred.12

Large Language Models (LLMs)

Although natural language are not specifically designed to advance life sciences, they will significantly impact how life science research is conducted by supporting education and training, basic research, and laboratory capabilities. Large language models can rapidly compile information from numerous sources and present it in accessible language. In essence, this effectively poses a “dual-use” problem, with LLMs providing knowledge that is used to inform legitimate science but can also be used for nefarious purposes.13 Currently, these models seem most beneficial for users with some basic knowledge of a subject, but several experts believe that they can also help individuals entirely unfamiliar with a topic quickly reach an understanding comparable to that of an undergraduate or even a doctoral student. According to the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) report,14 however, some experts found the tools lacking in precision and accuracy when dealing with more technically complex questions. They believe that current LLMs are unlikely to provide significant novel insights into biological systems. Some LLMs are trained specifically on scientific literature, and these may be more useful for students and others seeking to learn about technical topics.

There have been attempts to evaluate the risks involved15 and while these have suggested that current LLMs do not significantly increase biorisk, there has also been significant criticism of the study design and statistical methods used.16 It has also been suggested that these reports might suffer from asymmetric risk assessment where only the negative results of these evaluations are published (since positive results, showing the potential harm these models could pose, might be considered dangerous). This discrepancy could possibly be distorting our perception of actual risk.

Large language models could potentially aid in designing and troubleshooting molecular biology experiments based on published information and program robotics platforms to execute experiments. These capabilities can reduce the need for individuals to develop the technical skills necessary to perform the experiments themselves. While current LLMs are usually limited to text-based information, some models can incorporate information from images and videos, potentially enabling them to provide more effective feedback and suggestions for troubleshooting laboratory techniques in real time. These AI-based lab assistants would have many beneficial applications for helping researchers, especially those just starting their careers. However, the same AI-based assistants could also encourage laboratory work for nefarious purposes.

Biological Design Tools (BDTs)

The second category of AI tools with potential misuse risks comprises . It is anticipated that LLMs fine-tuned on biological data could emerge as the most potent BDTs. Large language models can be trained on DNA and RNA sequencing patterns to predict modifications and regulatory mechanisms within these sequences. In addition, LLMs pretrained on protein data can be used for various applications, such as predicting protein structures, generating new proteins, annotating protein functions, and predicting protein interactions. Currently, BDTs are often openly shared, whether they are developed by academia (e.g., RFDiffusion) or industry (e.g., ProGen2). While today’s BDTs are limited to creating proteins with relatively simple, single functions, future iterations are expected to be capable of optimizing proteins17 and enzymes with various functions. In addition to protein or organism design tools, there are other machine learning tools with dual-use implications, including those predicting properties such as immune evasion or advancing the functional understanding of the human genome. Deep learning architectures such as Enformer significantly enhance the accuracy of gene expression predictions from DNA sequences.18

Several experts fear that AI protein design tools would make it harder for DNA providers to maintain a comprehensive oversight of ordered DNA. Since current DNA screening methods are based on a comparison of the ordered DNA and that of a pathogen DNA, designed proteins could escape that check. These tools could aid the redesign of current hazards (to generate toxin or pathogen designs not found in nature) and evade DNA sequencing screening.19

AI-Enabled Automation of Life Sciences

In the most simplistic terms, AI-enabled automated science is understood as the delegation of one, several, or all steps in the scientific process to AI. According to the NTI report, at the time of their writing, there were several examples of research projects where at least one of each of the scientific processes had been automated. These steps include conducting the initial academic literature search, developing hypotheses, designing and performing experiments using robotics, analyzing results, and updating hypotheses. Each of these capabilities could significantly speed up the scientific process, offering opportunities to scale up, reducing the number of experiments needed, and limiting delays and errors caused by humans. The possibility of full automation of biological experiments is still largely debated.

A more recent approach to automated science involves developing autonomous capable of interacting with multiple AI tools (e.g., LLMs) to coordinate and complete complex tasks. One example from chemistry is ChemCrow,20 which is an LLM-based agent designed to carry out tasks across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and material design. These types of tools can be used to search the internet for relevant information, connect to the robotics via application programming interfaces (API), and even connect with other LLMs to delegate tasks, as was exemplified by the ibuprofen synthesis project.21

AI in Drug Design

There is currently a need to reduce the cost and time of drug discovery. Achieving this will facilitate the development of treatments for example for diseases which have received less research funding, such as tropical and orphan diseases, and will increase the availability of new drugs overall. Scientists are making progress with robot scientists such as Eve,22 a system that automated early-stage drug discovery to identify new treatments for neglected tropical diseases. Over the last few years, there has also been more discussion on how AI technologies for drug discovery could potentially be misused.23

Risk Mitigation and Governance

Experts have suggested several methods to address the risks posed by LLMs and BDTs. One of these is pre-release model evaluations. Characterizing risks and assessing the effectiveness of safeguards before models are released would incentivize developers to eliminate harmful model behavior throughout the training and deployment phases.

Another method, which takes into account the trade-offs, is balancing the need for unrestricted access with security concerns. Various stakeholders need to gather evidence and create tools to assess when the benefits of openly releasing a model are outweighed by the risks, perhaps also considering user authentication steps for more powerful models.

Characterizing risks and evaluating the effectiveness of protective measures before release would provide an incentive for developers to clean up harmful model behavior throughout the training and use phase.

Experts also recommend strengthening biosecurity measures at the interface between the digital and physical realms. Since access to synthetic DNA is crucial for converting biological designs into physical agents, industry leaders have voluntarily started screening gene synthesis orders (by verifying customers’ identities and monitoring orders to ensure sequences that could cause harm are not released inappropriately) and are advocating for a regulatory baseline. The Executive Order 14110 issued by the White House in October 2023 on AI marked a step in this direction by mandating the use of screened DNA in federally funded research. That said, the EU itself has not yet passed regulations on this issue. In June 2024 , a global baseline for nucleic acid synthesis screening was proposed, entitled the “Common Mechanism for DNA Synthesis Screening”.24 This tool was developed in collaboration with a technical consortium of experts in DNA synthesis, synthetic biology, biosecurity, and policy with a view to overcoming existing barriers. The Common Mechanism software employs multiple methods to identify sequences of concern, match them taxonomically to regulated pathogens, and clear benign genes for synthesis.

The end of 2023 brought several other new requirements for the powerful AI x Bio models in the US. The Executive Order mandates comprehensive measures to mitigate national security risks posed by AI systems. Companies developing “dual-use foundation models” must regularly report their model development plans and risk management strategies, including safeguarding model weights and conducting red-team tests to identify dangerous capabilities. Artificial intelligence models trained on biological sequence data are subject to new reporting and compliance requirements.

- Carter, S. R., Wheeler, N., Chwalek, S., Isaac, C., & Yassif, J. M. (2023). The Convergence of Artificial Intelligence and the Life Sciences: Safeguarding Technology, Rethinking Governance, and Preventing Catastrophe. Nuclear Threat Initiative. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/the-convergence-of-artificial-intelligence-and-the-life-sciences/ ↩

- Syrowatka, A., Kuznetsova, M., Alsubai, A., Beckman, A. L., Bain, P. A., Craig, K. J. T., Hu, J., Jackson, G. P., Rhee, K., & Bates, D. W. (2021, June 10). Leveraging artificial intelligence for pandemic preparedness and response: A scoping review to identify key use cases. Npj Digital Medicine, 4(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00459-8 ↩

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2018, December 17). New tools for public health experts: Outbreak detection and epidemiological reports. Europäische Union, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/new-tools-public-health-experts-outbreak-detection-and-epidemiological-reports ↩

- Njage, P. M. K., Henri, C., Leekitcharoenphon, P., Mistou, M., Hendriksen, R. S., & Hald, T. (2018). Machine Learning Methods as a Tool for Predicting Risk of Illness Applying Next‐Generation Sequencing Data. Risk Analysis, 39(6), 1397–1413. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13239; Zhao, A. P., Li, S., Cao, Z., Hu, P. J.-H., Wang, J., Xiang, Y., Xie, D., & Lu, X. (2024, June 2). AI for science: Predicting infectious diseases. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 5(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2024.02.002 ↩

- Ahmed, W., Angel, N., Edson, J., Bibby, K., Bivins, A., O’Brien, J. W., Choi, P. M., Kitajima, M., Simpson, S. L., Li, J., Tscharke, B., Verhagen, R., Smith, W. J. M., Zaugg, J., Dierens, L., Hugenholtz, P., Thomas, K. V., & Mueller, J. F. (2020, August 1). First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: A proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Science of The Total Environment, 728, 138764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764 ↩

- Eze, P. U., Geard, N., Mueller, I., & Chades, I. (2023). Anomaly Detection in Endemic Disease Surveillance Data Using Machine Learning Techniques. Healthcare, 11(13), 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131896; Ren, H., Li, Y., & Huang, T. (2023). Anomaly Detection Models for SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance Based on Genome k-mers. Microorganisms, 11(11), 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11112773 ↩

- Metsky, H. C., Welch, N. L., Pillai, P. P., Haradhvala, N. J., Rumker, L., Mantena, S., Zhang, Y. B., Yang, D. K., Ackerman, C. M., Weller, J., Blainey, P. C., Myhrvold, C., Mitzenmacher, M., & Sabeti, P. C. (2022, March 3). Designing sensitive viral diagnostics with machine learning. Nature Biotechnology, 40(7), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01213-5 ↩

- Alley, E. C., Turpin, M., Liu, A. B., Kulp-McDowall, T., Swett, J., Edison, R., Von Stetina, S. E., Church, G. M., & Esvelt, K. M. (2020, December 8). A machine learning toolkit for genetic engineering attribution to facilitate biosecurity. Nature Communications, 11(1), 6293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19612-0 ↩

- Carter et al., 2023. ↩

- Sandbrink, J. B. (2023). Artificial intelligence and biological misuse: Differentiating risks of language models and biological design tools (Version 8). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2306.13952 ↩

- Rose, S., & Nelson, C. (2023, October 18). Understanding AI-Facilitated Biological Weapon Development. The Centre for Long-Term Resilience. https://www.longtermresilience.org/post/report-launch-examining-risks-at-the-intersection-of-ai-and-bio ↩

- Toews, R. (2023, July 16). The Next Frontier For Large Language Models Is Biology. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robtoews/2023/07/16/the-next-frontier-for-large-language-models-is-biology/ ↩

- Sandbrink, 2023. ↩

- Carter et al., 2023. ↩

- Rose et al., 2023; Mouton, C., Lucas, C., & Guest, E. (2024, January 25). The Operational Risks of AI in Large-Scale Biological Attacks: Results of a Red- Team Study. (RAND). ↩

- Marcus, G. (2024, February 4). When looked at carefully, OpenAI’s new study on GPT-4 and bioweapons is deeply worrisome. Marcus on AI. https://garymarcus.substack.com/p/when-looked-at-carefully-openais ↩

- Spotlight on protein structure design. (2024, February 15). Nature Biotechnology, 42(2), 157–157. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02150-1 ↩

- Avsec, Ž., Agarwal, V., Visentin, D., Ledsam, J. R., Grabska-Barwinska, A., Taylor, K. R., Assael, Y., Jumper, J., Kohli, P., & Kelley, D. R. (2021). Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.07.438649 ↩

- Carter et al., 2023. ↩

- Bran, A. M., Cox, S., Schilter, O., Baldassari, C., White, A. D., & Schwaller, P. (2024, May 8). Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nature Machine Intelligence, 6(5), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00832-8 ↩

- Boiko, D. A., MacKnight, R., & Gomes, G. (2023, April 11). Emergent autonomous scientific research capabilities of large language models (Version 1). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2304.05332 ↩

- Williams, K., Bilsland, E., Sparkes, A., Aubrey, W., Young, M., Soldatova, L. N., De Grave, K., Ramon, J., De Clare, M., Sirawaraporn, W., Oliver, S. G., & King, R. D. (2015, March 6). Cheaper faster drug development validated by the repositioning of drugs against neglected tropical diseases. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 12(104), 20141289. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.1289 ↩

- Urbina, F., Lentzos, F., Invernizzi, C., & Ekins, S. (2022, March 7). Dual use of artificial-intelligence-powered drug discovery. Nature Machine Intelligence, 4(3), 189–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00465-9 ↩

- Wheeler, N. E., Carter, S. R., Alexanian, T., Isaac, C., Yassif, J., & Millet, P. (2024, June 20). Developing a Common Global Baseline for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening. Applied Biosafety, 29(2), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1089/apb.2023.0034 ↩