Artificial Intelligence, Semiconductors, and the Military

The development of processes in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) has burgeoned in recent years, driven in particular by global tech companies and research institutions. At the same time, the application of this dual-use technology in battlefield control and data analysis in Ukraine or for the large-scale selection of relevant military targets in Gaza demonstrates the growing importance of this technology for military actors. However, these applications also illustrate the challenges of this technology in terms of the limits of human control and the comprehensibility of automated decisions and underline the need for regulation. At the same time, the dominance of AI and semiconductor technologies and the availability of the underlying production chains is increasingly developing into a global power play.

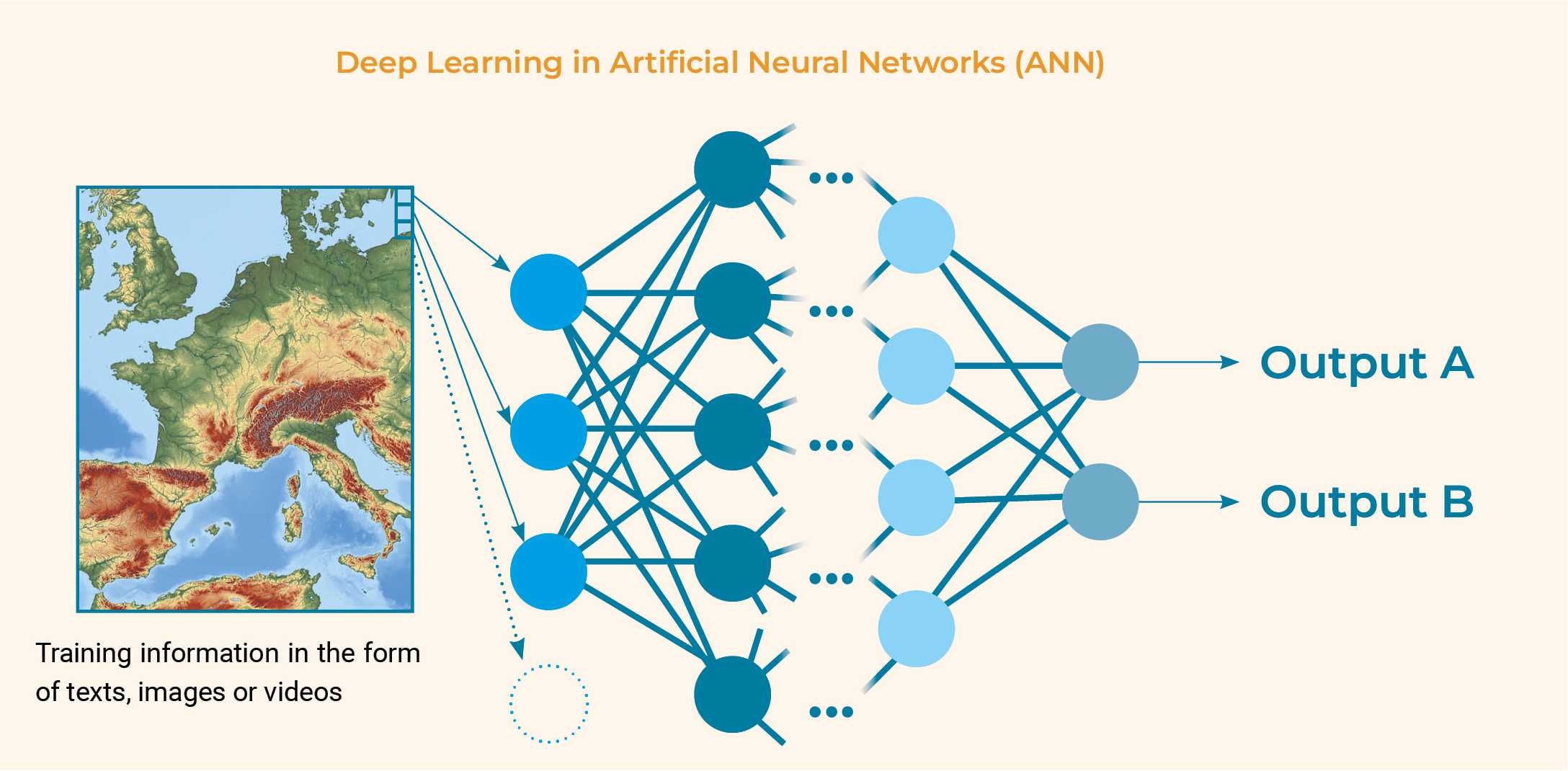

Even though and its subfield covers a wide variety of approaches, current AI systems are almost exclusively based on the concept of what are known as artificial neural networks (ANN). This approach, which is based on ideas from the 1940s, simulates the function and networking of human brain cells. Although already extensively researched in the 1980s and 1990s, it is only today’s semiconductor technologies and the production of highly powerful, inexpensive, and small chips that have achieved the kind of performance that, in conjunction with more efficient software architectures, can enable modern AI applications. Although approaches such as , , and do play a role in specific applications, in public debate, the term AI generally refers to ANN.

The key element of an AI application is the a data structure for storing digital information. This is developed in a using extensive data that is tailored to the desired problem-solving capability. The process in question is usually deep learning (DL). Here, models are either tailored to a specific task or pretrained in the form of foundation models, often marketed commercially, which are then optimized for the actual application context in further training processes using specific data. The quality and availability of training data is crucial when it comes to the achievable problem-solving ability of AI applications , which is why the data is often compiled by specialized companies, curated by hand, and sold on the market as an economic commodity. Current AI generations differ in terms of the kind of data that can be processed in training, during application, and for user interactions. While this distinction is increasingly becoming blurred, the world’s leading AI companies, like OpenAI, Meta, Microsoft or Anthropic, are working on what has been dubbed “artificial general intelligence” (AGI). The aim is for AGI to possess human-like cognitive abilities and thus be able to learn from experience, draw conclusions independently, and interact with other AI systems. When and whether this ambitious goal can be achieved, however, is disputed among experts.1

All these AI systems need enormous computational power to be trained and executed in a finished application. In contrast to cloud server centers, this is only possible with much more powerful chips that can be operated at full load and for longer periods of time. The newest generation of AI accelerators (the “GB200 architecture”) by market leader Nvidia, which combines an AI chip () with other necessary hardware, for instance has a power consumption of around 1,500 watts per unit with a continuous computing power of 45 * 10¹² operations per second.2 For comparison, an iPhone 14 manages approximately 1.4 * 10¹² operations per second in short load peaks.3 Artificial intelligence data centers, in which tens to hundreds of thousands of these devices are operated together, achieve a total power consumption of 100 megawatts and more.4 Since such server systems have to be equipped with the network infrastructures needed for internal data exchange as well as for the power supply and the enormously complex cooling of the systems, the production of these technical systems, their construction, and operation are extremely expensive.5

Military Applications of AI

The use of AI in Ukraine’s fight against Russia or in Israel’s war against Hamas has highlighted the dynamics of introducing new technologies with dual-use potential into military applications. In the first case, AI applications have emerged out of the situation and are embedded ad hoc into military processes and de facto tested, adapted, and expanded “in the field.” The example of Israel, on the other hand, illustrates the long-term strategic embedding of such applications into military decision-making processes, combined with the development of the necessary logistical and technical structures. What the two wars have in common, however, is that AI systems are predominantly used as a tool in tactical planning to support and accelerate decision-making through the automated aggregation and evaluation of a wide variety of data sources—what is referred to as “decision support” or “battlefield management systems.” While in Ukraine, these systems are used to predict troop movements, the Israeli systems “Lavender”6 and “Gospel”7 have become known in the course of the Gaza War and are used to identify physical objects as well as people and mark them as potentially relevant military targets. This application of AI can be seen as the step after the approach that has become known as big data, i.e., bringing together extensive data from modern military sensor technology, such as image and video data, as well as the movement profiles of targets, and processing them with technical support.8 This reduction in sensor-to-shooter time, which is understood as a tactical advantage from a military perspective,9 further increases the speed of warfare, while the role of human control and possibility of intervention are sidelined even more and the latter increasingly perceived as a bottleneck.10

The trend towards the autonomization of military weapon systems is also fueling the development and use of AI. On the one hand, such systems are supposed to be able to operate in unknown territory or under variable conditions and require the ability to react flexibly to situations rather than adhere to rigid instructions. Artificial intelligence systems provide these capabilities, which can for instance involve operating autonomously in a target area while taking obstacles into account or identifying military targets, even with noisy data sources. On the other hand, AI systems are capable of capturing patterns or deriving rules from data autonomously during the training process. This makes it possible for AI systems to learn highly complex skills, such as the control and aerial combat of fighter jets,11 without those skills needing to be explicitly formulated. In terms of technology, the fact that different AI systems can also be operated in a coupled manner comes into play here. For example, the evaluation of radar data, the identification of potential targets, or the navigation of a vehicle can be achieved by individual AI systems, and their outputs can then be combined in a comprehensive AI system for overall control.

In addition to these complex AI applications, some special capabilities are now so technologically advanced—such as image evaluation or speech analysis, which are now built into chips in every modern smartphone—that even small military devices such as quadrocopters can be equipped with them at a low cost, on a mass scale, and improved accordingly. This broad rollout enables applications such as those to be implemented in the US “Replicator” program,12 which envisages the large-scale, automated and autonomous deployment of swarms of drones—an idea that has recently also been discussed within NATO in the context of border security against Russia.13

Artificial intelligence is also playing an increasingly important role in cyberspace, for example, in the automated analysis of data transfers to identify unusual activities indicating cyberattacks, to detect malware, or to automatically trigger countermeasures.14 At the same time, AI can also be used to automatically generate new malware based on available databases of security vulnerabilities or to tailor it for selected targets.15

This ability of AI to generate new variants of a digitized dataset based on existing information is considered highly critical with regard to the production of new biological and chemical weapons.

Artificial intelligence is also discussed repeatedly with regard to the analysis of image and sensor data in the context of nuclear deterrence and the required monitoring and sensor infrastructures. As the speed of response in the event of a hypothetical nuclear attack is considered crucial for this application in particular, AI systems are to be used here to detect preparation for and activities related to a nuclear attack.16 At the same time, this scenario illustrates the danger of “escalation by mistake” and the imponderables of using a technology that is difficult to control or understand, even if it is “only” used to filter and analyze data.

To summarize, AI is seen by military actors as an enabling technology that optimizes existing applications or allows operational expansion in certain deployment scenarios. A key motive here is to gain tactical advantages by accelerating decision-making processes and securing information advantages. In connection with autonomous weapon systems, ways of reducing the risk of human casualties through the use of technical devices are also being considered. Artificial intelligence is also seen as a solution to a problem inherent in the increasing mechanization of the armed forces, namely that ever better weapons and sensor technology generally also generate increasingly large volumes of data that human operators struggle to handle.

To summarize, AI is seen by military actors as an enabling technology that optimizes existing applications or allows operational expansion in certain deployment scenarios.

Outlook and Recommendations

In view of the rapid progress of AI technology, states are currently debating, in various formats and often in close cooperation with representatives of AI tech companies, what responsible use of AI could look like and what type of regulation would be necessary for this.17 For military applications, in particular, these debates should be based firmly on the issues that have long been raised in the context of autonomous weapons systems, such as the possibilities of human control and responsibility and the compatibility of such systems with international law, as well as the risks to military stability between potential adversaries. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that even in an AI-supported application where the final decision is made by a human operator, the AI itself has made countless micro-decisions through processes of filtering and analysis that were neither explicitly and comprehensibly defined in the training process, nor are they transparent to the operator in the decision-making situation.18 Even if initial approaches to what has been dubbed 19 attempt to resolve the “black-box” nature of AI, they are not even close to reaching the required level of explainability offered by human reasoning processes. Further, these approaches generally lead to a reduction in the performance and reaction speed of AI systems, i.e., the main advantages of this technology, and are unlikely to be able to establish themselves without binding legal requirements.

Yet, initial government initiatives regulating military AI are also highlighting divergences, particularly between countries that are part of the highly centralized AI production chains, such as the USA, UK, Netherlands, and Taiwan, as well as countries that are not currently participating, especially China. However, in view of the strong centralization and global dependence on semiconductor manufacturing companies in Taiwan, such as TSMC (known as “foundries”), this development also increases concerns about growing international tensions. This is particularly evident in the form of the “chip wars.” This battle to control the semiconductor industry is being used by the USA, on the one hand, in an attempt to prevent Chinese manufacturers from accessing specialized AI chips and the necessary know-how, manufacturing equipment, materials, and production chains,20 and, on the other, to try and protect its ally Taiwan from China’s claim to sovereignty through special mechanisms such as kill switches in chip manufacturing plants21—which would destroy the devices if necessary.

Irrespective of individual views on these measures, the USA also demonstrates that there certainly are possible approaches for regulating AI systems. For example, the “Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence” (Executive Order 14110 of 2023) defines technically measurable parameters, such as the total computing power required to train or run an AI system, as the basis for US export controls on such devices and finished AI products. In view of these starting points, combined with the aspect that, despite the digital nature of AI applications, it is primarily the specialized server and network devices that make powerful AI systems possible, there may still be opportunities for arms control. For this to happen, however, other countries would also have to take up, develop, and support these impulses.

- Fjelland, R. (2020). Why general artificial intelligence will not be realized. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0494-4 ↩

- Spille, C. (2024, March 18). Blackwell: Nvidia enthüllt seine nächste KI-Beschleuniger-Generation. heise online. https://www.heise.de/news/Nvidias-neue-KI-Chips-Blackwell-GB200-und-schnelles-NVLink-9658475.html ↩

- Owen, M. (2022, September 26). How iPhone speeds have grown in the last 5 years. appleinsider. https://appleinsider.com/articles/22/09/26/how-iphone-speeds-have-grown-in-the-last-5-years ↩

- Patel, D., & Nishball, D. (2024, June 17). 100k H100 Clusters: Power, Network Topology, Ethernet vs InfiniBand, Reliability, Failures, Checkpointing. SemiAnalysis. https://www.semianalysis.com/p/100000-h100-clusters-power-network ↩

- Patel & Nishball, 2024. ↩

- Abraham, Y. (2024, April 3). ‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza. 972 Magazine. https://www.972mag.com/lavender-ai-israeli-army-gaza/ ↩

- Davies, H., McKernan, B., & Sabbagh, D. (2023, December 1). ‘The Gospel’: How Israel uses AI to select bombing targets in Gaza. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/01/the-gospel-how-israel-uses-ai-to-select-bombing-targets ↩

- RAFAEL Advanced Defense Systems LTD. (2019). FIRE WEAVER - Tactical Networked Sensor-to-Shooter System. https://www.rafael.co.il/system/fireweaver/ ↩

- Skove, S. (2024, March 7). Targeting time shrinks from minutes to seconds in Army experiment. DefenseOne. https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2024/03/targeting-time-shrinks-minutes-seconds-army-experiment/394758/ ↩

- Deutscher Ethikrat. (2023). Mensch und Maschine – Herausforderungen durch Künstliche Intelligenz—Stellungnahme des Deutschen Ethikrates. https://www.ethikrat.org/fileadmin/Publikationen/Stellungnahmen/deutsch/stellungnahme-mensch-und-maschine.pdf ↩

- Copp, T. (2024, April 5). An AI-controlled fighter jet took the Air Force leader for a historic ride. What that means for war. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2024/05/04/an-ai-controlled-fighter-jet-took-the-air-force-leader-for-a-historic-ride-what-that-means-for-war-00156147 ↩

- Katz, J. (2024, January 20). Replicator’s ‘PRIME’ time: DIU seeks small USV interceptors ready for rapid production. Breaking Defense. https://breakingdefense.com/2024/01/replicators-prime-time-diu-seeks-small-usv-interceptors-ready-for-rapid-production/ ↩

- Milne, R. (2024). Six Nato countries plan ‘drone wall’ to defend borders with Russia. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/949db465-cd27-4c66-9908-c2faa80b602b ↩

- Jun, J. (2024, April 30). How Will AI Change Cyber Operations?. War on the Rocks. https://warontherocks.com/2024/04/how-will-ai-change-cyber-operations ↩

- Fang, R., Bindu, R., Gupta, A., Zhan, Q., & Kang, D. (2024, June 2). Teams of LLM Agents can Exploit Zero-Day Vulnerabilities (arXiv:2406.01637). arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.01637 ↩

- Topychkanov, P. (2019, May). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Strategic Stability and Nuclear Risk. In South Asian Perspectives (Band 1). SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/publications/2019/research-reports/impact-artificial-intelligence-strategic-stability-and-nuclear-risk-volume-i-euro-atlantic ↩

- Reinhold, T. (2024, May 7). Der militärische Einsatz künstlicher Intelligenz braucht Regeln: Nur welche, darüber besteht keine Einigkeit. PRIF Blog. https://blog.prif.org/2024/05/07/der-militaerische-einsatz-kuenstlicher-intelligenz-braucht-regeln-nur-welche-darueber-besteht-keine-einigkeit ↩

- Heaven, W. D. (2024, March 4). Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/03/04/1089403/large-language-models-amazing-but-nobody-knows-why/ ↩

- Barredo Arrieta, A., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Del Ser, J., Bennetot, A., Tabik, S., Barbado, A., Garcia, S., Gil-Lopez, S., Molina, D., Benjamins, R., Chatila, R., & Herrera, F. (2020). Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information Fusion, 58, 82–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2019.12.012 ↩

- Shepardson, D., & Nellis, S. (2024, May 8). Intel, Qualcomm say exports to China blocked as Beijing objects. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/intel-flags-revenue-hit-us-revokes-certain-export-licenses-chinese-customer-2024-05-08 ↩

- Bloomberg. (2024, May 22). ASML and TSMC can disable EUV machines. Taipei Times. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2024/05/22/2003818194 ↩